An elephant never forgets

A younger rival may have learned how to sabotage those showers by disrupting water flow.

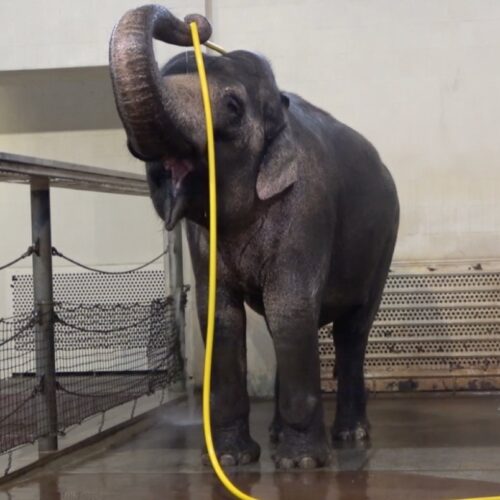

An elephant named Mary has been filmed using a hose to shower herself.

Credit:

Urban et al./Current Biology

Mary the elephant shows off her hose-showering skills. Credit: Urban et al./Current Biology

An Asian elephant named Mary living at the Berlin Zoo surprised researchers by figuring out how to use a hose to take her morning showers, according to a new paper published in the journal Current Biology. “Elephants are amazing with hoses,” said co-author Michael Brecht of the Humboldt University of Berlin. “As it is often the case with elephants, hose tool use behaviors come out very differently from animal to animal; elephant Mary is the queen of showering.”

Tool use was once thought to be one of the defining features of humans, but examples of it were eventually observed in primates and other mammals. Dolphins have been observed using sea sponges to protect their beaks while foraging for food, and sea otters will break open shellfish like abalone with rocks. Several species of fish also use tools to hunt and crack open shellfish, as well as to clear a spot for nesting. And the coconut octopus collects coconut shells, stacking them and transporting them before reassembling them as shelter.

Birds have also been observed using tools in the wild, although this behavior was limited to corvids (crows, ravens, and jays), although woodpecker finches have been known to insert twigs into trees to impale passing larvae for food. Parrots, by contrast, have mostly been noted for their linguistic skills, and there has only been limited evidence that they use anything resembling a tool in the wild. Primarily, they seem to use external objects to position nuts while feeding.

And then there’s Figaro, a precocious male Goffin’s cockatoo kept in captivity and cared for by scientists in the “Goffin lab” at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna. Figaro showed a surprising ability to manipulate single tools to maneuver a tasty nut out of a box. Other cockatoos who repeatedly watched Figaro’s performance were also able to do so. Figaro and his cockatoo cronies even learned how to combine tools—a stick and a ball—to play a rudimentary form of “golf.”

Shower time

Both captive and wild elephants are known to use and modify branches for fly switching. Brecht’s Humboldt colleague, Lina Kaufman, is the one who first observed Mary using a hose to shower at the Berlin Zoo and told Brecht about it. They proceeded to undertake a more formal study of the behavior not just of Mary, but two other elephants at the zoo, Pang Pha and her daughter Anchali. Mary was born in the wild in Vietnam, while Pang Pha was a gift from Thailand; Anchali was born at the Berlin Zoo, where she was hand-raised by zookeepers. Showering was part of the elephants’ morning routine, and all had been trained not to step on the hoses.

Mary’s rival Anchali blocking the flow of water. Urban et al./Current Biology

All the elephants used their trunks to spray themselves with water, but Mary was the only one who also used the hose, picking it up with her trunk. Her hose showers lasted about seven minutes, and she dropped the hose when the water was turned off. Where she gripped the hose depended on which body part she was showering: she grasped it further from the end when spraying her back than when showering the left side of her body, for instance. This is a form of tool modification that has also been observed in New Caledonian crows.

And the hose-showering behavior was “lateralized,” that is, Mary preferred targeting her left body side more than her right. (Yes, Mary is a “left-trunker.”) Mary even adapted her showering behavior depending on the diameter of the hose: she preferred showering with a 24-mm hose over a 13-mm hose and preferred to use her trunk to shower rather than a 32-mm hose.

It’s not known where Mary learned to use a hose, but the authors suggest that elephants might have an intuitive understanding of how hoses work because of the similarity to their trunks. “Bathing and spraying themselves with water, mud, or dust are very common behaviors in elephants and important for body temperature regulation as well as skin care,” they wrote. “Mary’s behavior fits with other instances of tool use in elephants related to body care.”

Perhaps even more intriguing was Anchali’s behavior. While Anchali did not use the hose to shower, she nonetheless exhibited complex behavior in manipulating the hose: lifting it, kinking the hose, regrasping the kink, and compressing the kink. The latter, in particular, often resulted in reduced water flow while Mary was showering. Anchali eventually figured out how to further disrupt the water flow by placing her trunk on the hose and lowering her body onto it. Control experiments were inconclusive about whether Anchali was deliberately sabotaging Mary’s shower; the two elephants had been at odds and behaved aggressively toward each other at shower times. But similar cognitively complex behavior has been observed in elephants.

“When Anchali came up with a second behavior that disrupted water flow to Mary, I became pretty convinced that she is trying to sabotage Mary,” Brecht said. “Do elephants play tricks on each other in the wild? When I saw Anchali’s kink and clamp for the first time, I broke out in laughter. So, I wonder, does Anchali also think this is funny, or is she just being mean?

Current Biology, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.017 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior reporter at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.