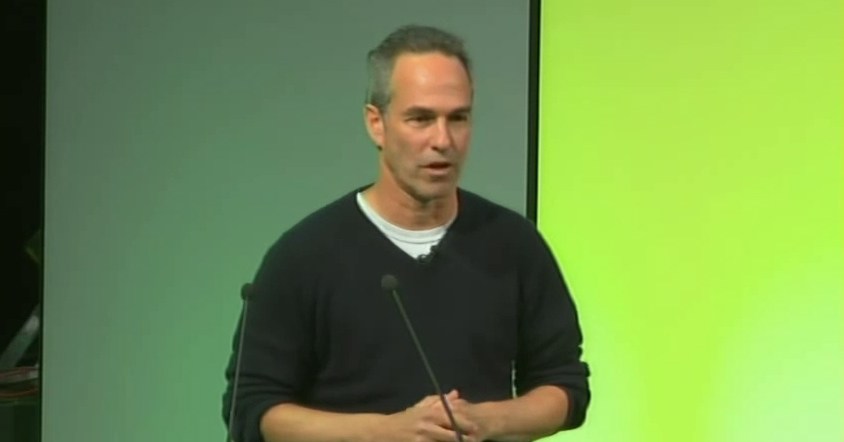

Danny Bilson joined now-bankrupt publisher THQ in 2008 to help shift it from a licensed and kids’ games company to a core games publisher, but the company “couldn’t change fast enough,” he said yesterday at the GameHorizon conference.

When he arrived at THQ as executive vice president of core games, the company had 17 different studios, but “six of them didn’t know what they were making,” said Bilson. So he was tasked with visiting the teams and helping them figure out what to work on, a process he described as “the most awesome job I’ve ever had in my life.”

But about eight weeks into his tenure, he was told the company had to cut about half of its production budget, which meant that the promising projects he had just greenlit would have to be killed. Bilson’s bosses gave him the option to leave at that point, but he told them he wanted to try to make it work anyway. THQ decided to close seven studios at the time, and Bilson described the process as “one of the worst things I’ve ever experienced,” although as the head of creative, he was spared the task of having to visit the studios and tell them they were being closed himself.

THQ later gave Bilson control of both the production and marketing departments, an opportunity he took to fix what he saw as a major problem: the “antagonistic” relationship between those two divisions. He considers that shift one of his biggest successes at THQ, because it produced “quality marketing that the developers [didn’t] hate.”

Bilson left the company in late May 2012, and said that he didn’t know what happened between then and the start of THQ’s bankruptcy proceedings in December.

“It’s hard for me — I gave it all I had, but it didn’t work”

“When I left, there was no talk of bankruptcy; there was no talk of anything like that,” he said. “It was really tough times, and we were trying to sell stuff off, but we were determined to live to fight another day, and we had a portfolio of games that people were really responding to.” Bilson also pointed out that the games in question — titles including Darksiders 2, Metro: Last Light and Company of Heroes 2 — were all projects that he had greenlit, and that he’s glad they got picked up and will be released eventually. Upon the company’s first bankruptcy auction this past January, he told Polygon that the closure of THQ was “a loss for gamers everywhere.”

“It’s hard. It’s hard for me — I gave it all I had, but it didn’t work, and I think they couldn’t change fast enough from a culture of kids’ licensed games to a culture of core games,” said Bilson. “And then, the business was changing faster than we could change.”

Update: Bilson also provided some information on his unannounced future projects, noting that it took him some time to figure out his post-THQ career.

“After that rough ride of four and a half years, I really didn’t know what I wanted to do,” he explained.

Bilson realized he had spent his career trying to combine films and games in a number of ways, so that’s what he’s working on now: “high-concept, micro-budget movie and connected game series,” which he believes is something that hasn’t really been tried before and wasn’t really possible until today’s media and technology climate.

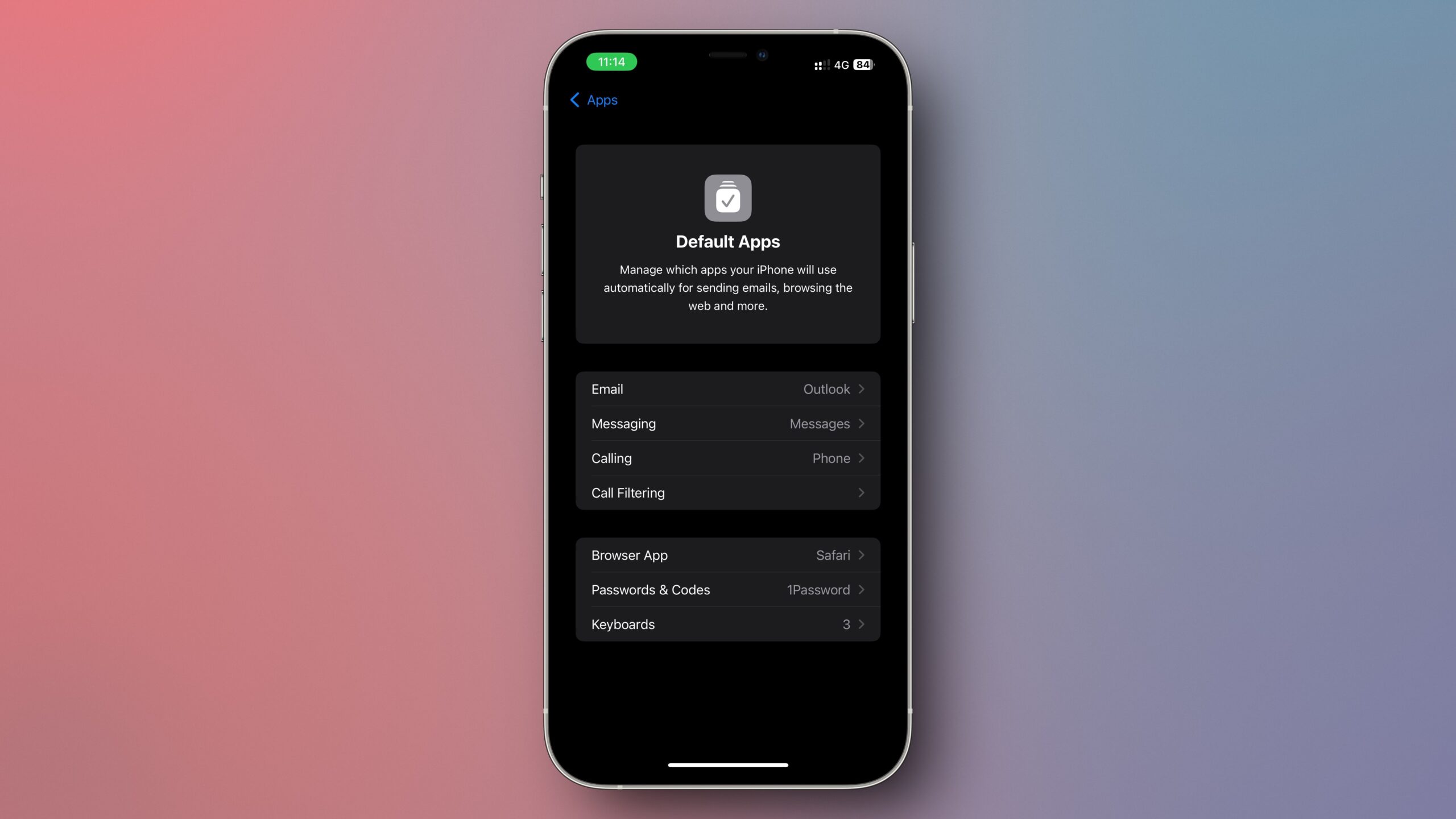

“The hardware now enables us to play the game and watch the film on the same device,” Bilson pointed out. He’s partnering with longtime film producer Lloyd Levin (Boogie Nights, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, Hellboy, The Watchmen) for transmedia properties in science fiction, horror and fantasy — all genres that lend themselves well to video games.

there has always been “a huge wall between the film guys and the game guys”

Bilson and his teams plan to produce movie-like content with three two-hour “episodes” a year, and fill the gaps with narrative games like Telltale’s The Walking Dead that keep the story going. The games will let players participate in the narrative, to a point, and “rejoin” the story by watching the next episodic film. The same writers will handle both projects, and the games and films will appear on consoles, computers, tablets and other “digital devices,” said Bilson.

“No one has ever been able to literally move the story from linear to interactive-ish linear … and back to linear,” he said, because there has always been “a huge wall between the film guys and the game guys.” The makers of Bilson’s projects will be “building both pieces under the same roof, with the same producers.”

Bilson closed by pointing out that even if the projects aren’t successful, the risk isn’t nearly as high because the budgets are smaller than with typical standalone films and games.

“The price of entry is nothing like the kind of dice I was rolling in my last job,” he said.